Before Wearing Blue Sapphire, Read This – 90% People Make This Mistake

Before you pick a stone linked to the sixth planet from the Sun, know what you’re really choosing. This guide explains how that gas giant fits into our solar system and why it matters to anyone curious about space and science.

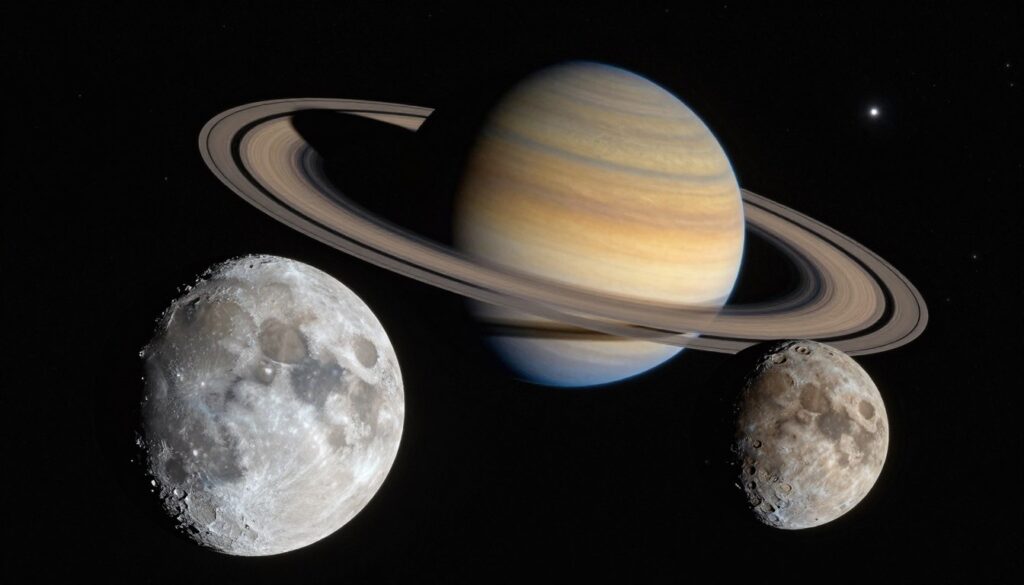

The sixth planet is made mostly of hydrogen and helium and has a striking ring system and dozens of moons. We’ll use images and mission data from Cassini, Voyager, and Pioneer to explore its upper atmosphere, cloud tops, and deep interior in plain language.

Expect clear context on magnetic field behavior, rotation and day-length cycles measured in hours and days, and how ring dynamics evolve over years. We’ll also flag common myths about rings, moons, and what “surface” means on a gas giant.

Read on to avoid the usual mistakes and to learn how mission findings connect to real science you can trust.

Key Takeaways

- Position: The sixth planet sits well beyond the inner planets in our solar system.

- Composition: It’s a gas giant made mostly of hydrogen and helium with bright rings.

- Missions matter: Cassini, Voyager, and Pioneer provide core images and data.

- Systems: Rings, moons, and magnetosphere form an interconnected mini system.

- Read carefully: Learn what “surface” means for a planet without solid ground.

Saturn

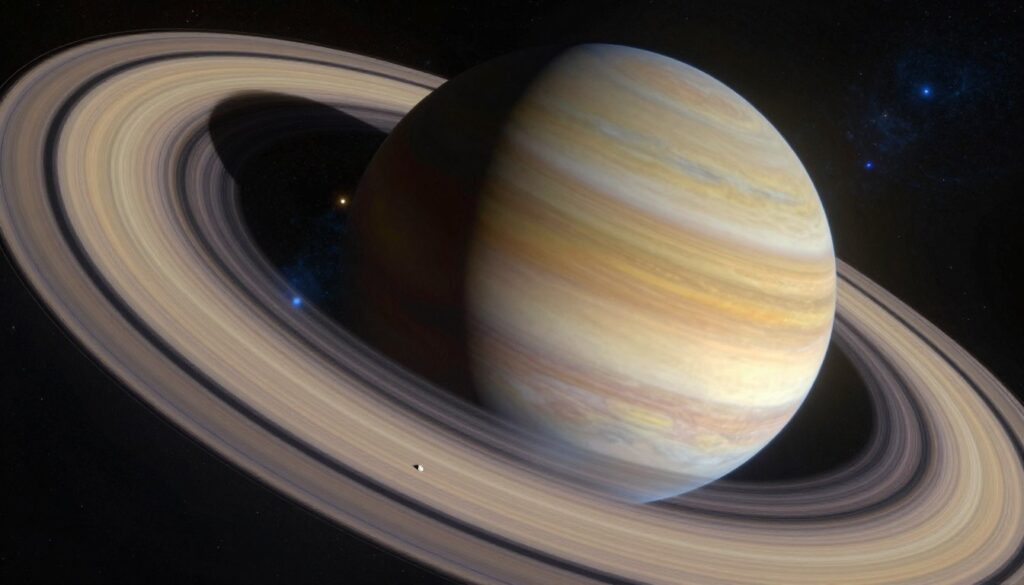

This massive member of our solar family shows how a gas-rich composition shapes size, shape, and weather. The world spins quickly, giving it an oblate silhouette: an equatorial radius of 60,268 km versus a polar radius of 54,364 km. That difference makes the planet look noticeably flattened.

Atmosphere and composition: The envelope is mostly hydrogen with helium and traces of methane, ammonia, and hydrocarbons. These gases create subtle banded clouds and a warm, golden hue visible through telescopes.

How this affects the system: Its low density and fast rotation influence gravity, weather, and seasonal sunlight. The planet’s size and gas layers also shape ring and moon dynamics without needing a solid surface.

| Attribute | Value | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Equatorial radius | 60,268 km | Shows overall size and bulge from rotation |

| Polar radius | 54,364 km | Indicates flattening and internal dynamics |

| Atmosphere | H2, He, methane, ammonia | Drives color, clouds, storms, and heat flow |

Think of this body as both a single planet and a complex system. Later sections dive into shape, internal layers, and how gas chemistry drives storms and long-term climate cycles.

The Sixth Planet from the Sun: Where Saturn Sits in the Solar System

Orbit and position: Orbiting the Sun at roughly 1.43 billion kilometers (about 891 million miles), the sixth planet sits well beyond Mars and Jupiter in the solar system’s outer reaches. Its semi-major axis is about 1,433.53 million km (9.58 AU), which defines a long, slow path around the Sun.

Distance, speed, and neighborhood

The planet moves at an average speed of 9.68 km/s as it circles the star. That pace is much slower than inner planets, which sweep around faster closer to the Sun.

Orbital timing: One sidereal orbit lasts about 29.4475 years — roughly 10,755.70 days — so seasons span many Earth years. Rotation remains fast: the world spins in hours even while its orbit takes decades.

- Orbital inclination is ~2.485°, which slightly tilts the orbit versus Earth’s plane and affects how the system looks at opposition.

- A near 5:2 resonance with Jupiter helps shape long-term orbital stability across the planet solar neighborhood.

- Angular diameter ranges from 14.5″ to 20.1″ (excluding rings), so apparent size changes with distance and viewing geometry.

| Metric | Value | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-major axis | 1,433.53 million km / 9.58 AU | Shows how far the planet is from the Sun and mission planning constraints |

| Average speed | 9.68 km/s | Comparison to inner planets; influences travel time and encounter planning |

| Orbital period | 29.4475 years / 10,755.70 days | Determines seasonal cycles and long-term observation windows |

| Inclination | 2.485° | Changes ring illumination and visibility from Earth |

Why this matters: These distances and timings explain why missions use gravity assists, why observation windows open only at certain times, and how the planet’s place in the system shapes ring shadows and seasonal lighting.

Gas Giant Basics: Size, Shape, and What Makes Saturn Different

How a gas giant looks from afar results from fast rotation and a mix of light gases under pressure.

Oblate spheroid shape: Rapid spin makes the equator bulge and the poles flatten, producing a noticeable oblate profile with a flattening of about 0.09796.

Size in miles and kilometers

The equatorial radius is 60,268 km (37,449 mi) while the polar radius is 54,364 km (33,780 mi).

This yields a massive volume of roughly 8.27×10^14 km3 — about 764 Earths — so the planet’s size is enormous compared to terrestrial worlds.

Composition, density, and surface gravity

The world is made mostly of hydrogen and helium, which explains why its mean density is only 0.687 g/cm3 — lighter than water despite a huge mass (5.6834×10^26 kg).

Surface gravity at the equator is about 8.96 m/s2 and the escape velocity is ~35.5 km/s. These values help the planet keep light gases even with low mean density.

- No hard surface: “Surface” here means cloud tops at standard pressure levels, not solid ground.

- Weather link: The large size and oblate shape drive strong banding and extreme winds.

- Interior hint: Hydrogen and helium behavior under pressure leads toward metallic hydrogen deeper down, which we will explore next.

Inside Saturn: Core, Metallic Hydrogen, and Internal Heat

Deep inside this giant, pressure and heat transform common gases into exotic, conductive forms.

Rocky core: Models place a heavy rocky core at roughly 9–22 Earth masses. It may be diffuse and span ~60% of the planet’s radius. That dense center helps anchor the whole system and affects gravity measurements.

Layers and conductive states

Under extreme pressure, hydrogen becomes metallic hydrogen and conducts electricity. Above that sits a layer of liquid hydrogen and helium, then the gaseous atmosphere near the cloud-top surface.

Helium rain and excess heat

Helium separates from hydrogen and sinks as droplets, releasing heat as it falls. This process, plus slow gravitational compression, explains why the world radiates about 2.5× the energy it gets from the Sun.

- Magnetic field: Currents in metallic hydrogen likely power the global magnetic field.

- Interior heat drives convection, which links to banding and giant storms seen in the atmosphere.

- Model uncertainties persist; gravity data and ring seismology keep refining core and layer estimates.

Atmosphere and Weather: From Upper Atmosphere Haze to Megastorms

From thin upper hazes to planet-encircling tempests, the atmosphere hosts dramatic changes across latitudes.

Composition: By volume, the mix is ~96.3% hydrogen and ~3.25% helium, with trace methane, ammonia, ethane, and other hydrocarbons. These gases and photochemical products create hazes that tint bands and polar regions.

Cloud layers, temperatures, and wind speeds

The visible cloud decks stack by pressure: ammonia ice near 0.5–2 bar (about 100–160 K), ammonium hydrosulfide around 3–6 bar, and deeper water clouds from ~2.5–9.5 bar (185–270 K).

Jet streams race at peak speeds near 1,800 kilometers per hour (about 1,100 miles per hour). These winds shape banding and shear that spawn long-lived storms.

Megastorms, seasons, and blue hues

Great White Spots are rare, planet-encircling megastorms that erupt roughly once per the planet’s orbital year. Seasonal sunlight, combined with rapid rotation and internal heat, times these events and shifts band brightness.

Rayleigh scattering sometimes gives the upper atmosphere a blue tint, especially in the north where thinner haze reveals molecular scattering.

- Internal heat powers convection that fuels storms and sustains long-lived vortices.

- Photochemistry creates colored hazes and latitude-dependent contrasts.

- How we measure it: spectrometers, thermal mapping, and long-term imaging across times and days reveal dynamics and temperature structure.

Polar features like the hexagon and vortex systems are extensions of these same forces, showing how layered gas, rotation, and sunlight produce extreme weather at high latitudes.

Saturn’s Hexagon and Polar Vortices: Extreme Weather at the Poles

A vast hexagonal wave hugs the polar region, circling the pole with surprising regularity. This north pole hexagon sits near 78°N and has sides about 14,500 km long—each side is larger than Earth’s diameter.

Hexagon dynamics and timing

The hexagon rotates with a period of about 10h 39m 24s. That rotation matches internal radio rotation times, hinting that deep layers link to surface jets.

South pole vortex contrasts

The south pole hosts a hurricane-like vortex with an eyewall and warm core. Winds reach near 550 km/h, which is like a category 4 storm but centered on the pole.

- Standing wave: Lab experiments show polygonal flows form when fluids rotate at different speeds, supporting a standing-wave origin.

- Scale: Large sides imply massive polar jet streams in the atmosphere and strong coupling across the system.

- Seasonal effects: High-latitude sunlight and seasonal shifts change cloud clarity and how these features appear over times.

Why it matters: Polar weather gives clues about deeper layers and the planet’s internal dynamics. Combining imaging, radio data, and thermal maps builds a coherent picture of these extreme features.

The Ring System: Structure, Cassini Division, and Ring Lifetimes

From narrow gaps to dense bands, the rings form a dynamic disk shaped by gravity, impacts, and tiny moonlets. The main architecture runs A, B, and C bands, with the Cassini Division separating the bright A and B regions. Within those broad lanes are thousands of finer structures: gaps, spiral density waves, and sharp edges carved by embedded bodies.

What the particles are made of

The rings are mostly water ice, with sizes from micrometer dust to mountain-scale chunks. Small moonlets and shepherd moons create propeller features and waves. These interactions shape texture, opacity, and the narrow gaps that appear in high-resolution images.

Origins, spacecraft discoveries, and lifetimes

Leading origin ideas include tidal breakup of a large moon or remnants from formation. Cassini’s Grand Finale measured ring mass to be under a Mimas-mass, supporting a surprisingly young age—likely under 100 million years.

Ring rain steadily removes material: charged water products spiral along magnetic field lines into the upper atmosphere. Micrometeoroid darkening and dynamical spreading fight processes that refresh or brighten the disk.

- Viewing geometry changes how the ring system looks from space and Earth.

- Spacecraft flybys transformed our view by revealing spiral waves and propeller gaps.

- Ongoing observations will refine mass-loss rates and lifetime estimates.

Moons of Saturn: A Diverse System of Worlds

Hundreds of natural satellites, from tiny moonlets to large, ocean-bearing worlds, circle the planet. This family of moons offers a compact lab for studying formation, geology, and potential habitability.

Counts and sizes

More than 274 moons are known, plus countless ring moonlets. Some are named and studied closely; many tiny bodies remain cataloged only by number.

Titan’s secrets

Titan is larger than Mercury and has a thick nitrogen-rich atmosphere with methane and ethane lakes on its surface. Radar and gravity data also point to a likely subsurface ocean.

Enceladus and active plumes

Enceladus (~500 km wide) vents water-rich plumes that carry organics into space. Those geysers feed a faint ring and make this moon a top target in the search for life.

Photogenic oddballs

Iapetus shows a strange two-tone surface. Hyperion is sponge-like and tumbling. Mimas, Pan, Dione, and Rhea each display unique craters, grooves, or ring-clearing roles.

- Why it matters: The diversity of moons helps us test ideas about oceans, atmospheres, and how a planet shapes satellite evolution.

- Upcoming missions will revisit key moons with new sensors and landing plans.

Magnetic Field and Magnetosphere: How Saturn Shapes Space Around It

A deep, internal dynamo creates the global magnetic field that surrounds this gas giant.

Origin and strength

Electric currents in metallic hydrogen drive a dynamo. These currents produce an equatorial field near 0.2 gauss (20 μT), weaker than Jupiter’s and slightly weaker than Earth’s.

Magnetosphere and auroras

The resulting magnetosphere carves a bubble into space, deflecting solar wind and creating auroras at the poles when charged particles hit the upper atmosphere.

“Voyager and Cassini tracked boundary crossings and mapped field lines, revealing a dynamic, changing bubble.”

| Feature | Value / Effect | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Equatorial field | ~0.2 gauss (20 μT) | Sets auroral energy and particle motion |

| Source | Metallic hydrogen dynamo | Drives global currents and radio signals |

| External drivers | Solar wind pressure | Changes magnetosphere size and shape |

| Moon input | Titan adds plasma | Alters local particle populations |

Ring interactions channel charged water into the upper layers, feeding “ring rain” that links the rings and the atmosphere. Spacecraft radio emissions helped resolve rotation and revealed how magnetic processes modulate signals.

Why it matters: Magnetospheres shape local system weather, protect moons, and control energy flow—key to understanding this planet‘s environment and space weather across the outer solar system.

Orbit, Rotation, and Seasons: The Rhythm of a Gas Giant

At great distance from the Sun, years last decades while days race by in mere hours. A sidereal orbit runs about 29.4475 years (≈10,755.7 days), and the synodic cycle is ~378.09 days. The small axial tilt of ~2.485° still creates slow but visible seasons across cloud bands and rings.

Orbital timing and seasonal effects

Long orbital years mean seasons change over many Earth years. Ring illumination, storm frequency, and polar haze evolve with those slow seasonal times.

Multiple rotation measures

Researchers use several rotation systems because different layers and methods give different answers. System I tracks equatorial winds (~10h14m). System II measures mid-latitudes (~10h38m25s). System III comes from radio methods (~10h39m22s).

| Metric | Value | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Sidereal period | 29.4475 years | Sets long seasonal cycles |

| Synodic period | 378.09 days | Timing for observation windows from Earth |

| Seismology signal | ~10h33m38s | Probes deep interior rotation |

| Cassini radio | ~10h45m45s (variable) | Shows magnetic field drag, possibly from an active moon |

Cassini found radio periods varied, challenging assumptions about a single internal spin. Evidence suggests an active saturn moon, Enceladus, injects plasma that can drag field lines and skew radio times.

Why it matters: Reconciling atmospheric winds, magnetic signals, and ring seismology helps constrain interior models and core size. Continuous observations across days and years remain key to tracking true rotation and seasonal changes.

From Pioneer and Voyager to Cassini: Spacecraft That Revealed Saturn

Close encounters in the late 1970s and early 1980s replaced sketches with high-resolution images and hard data.

Pioneer 11 performed the first close pass in 1979, giving scientists baseline measurements that guided later missions.

Voyager spacecraft 1 and 2 followed in 1980–81. Their cameras and spectrometers returned dramatic images and breakthrough measurements of rings, moons, and atmospheric structure.

Pioneer 11, Voyager 1 and 2: first close looks and breakthrough data

The twin Voyager probes mapped clouds, discovered new moons, and revealed fine ring structure. Their radio and magnetometer readings offered the first clues about internal rotation and the magnetic environment.

Cassini spacecraft and Huygens: mapping rings, moons, and atmosphere

The Cassini spacecraft orbited from 2004 to 2017, spending years building a coherent picture of the system.

Its instruments—radar, spectrometers, imagers, and magnetometers—pierced Titan’s haze, mapped rings in detail, and sampled Enceladus plumes where organics were found.

“Long-duration missions let scientists watch seasonal change and link imaging, radar, and particle data into a unified view.”

Why it matters: These collaborative missions turned isolated snapshots into continuous study, set up the Grand Finale Phase, and reshaped questions about habitability, ring age, and interior structure.

Cassini’s Grand Finale: New Data on Rings, Mass, and Saturn’s Interior

In its Grand Finale, Cassini threaded narrow corridors that let scientists weigh and sample the ring system directly.

Ring mass, brightness, and hints of youthful rings

Close dives measured tiny gravitational tugs on the cassini spacecraft to estimate ring mass. Those pulls proved the rings are lighter than expected—less than the mass of Mimas. Low mass plus high brightness points to relatively young rings in planetary years, not primordial leftovers.

Close passes between rings and cloud tops: unprecedented space science data

Images and in-situ sampling near the ring plane revealed particle sizes from dust to meter-scale chunks. Fields-and-particles instruments recorded charged dust and plasma that link ring particles to the upper atmosphere.

Magnetic field readings during the dives helped constrain interior conductivity and rotation. Data showed how ring rain and charged particles feed atmosphere chemistry.

- Precise navigation turned tiny trajectory shifts into a scale for ring mass.

- Close sampling gave the only direct view of particle structure and ring–atmosphere exchange.

- Results refocused ideas: breakup of a moon versus slow, primordial decay now have different timelines.

Why it matters: These daring passes delivered space science data impossible from afar and reshaped timelines for ring evolution and models of the planet’s interior.

What’s Next: Dragonfly to Titan and the Future of Saturn Exploration

Dragonfly will be a flying lander that hops across Titan to study prebiotic chemistry up close.

Planned to launch in June 2027, Dragonfly is a rotorcraft designed to sample surface organics, map diverse terrains, and look for habitability indicators on this cold moon.

Mission goals and timeline

The team will fly short hops to collect chemistry and geologic data. The mission will take years of cruise and operations to reach objectives and build a layered view of Titan’s surface.

Why it matters to planetary and exoplanet science

The saturn system serves as a natural lab for comparing ocean worlds, ring dynamics, and atmospheric chemistry. Dragonfly builds on the maps and atmosphere profiles from the cassini spacecraft to pick landing sites and refine experiments.

- Technological leap: a rotorcraft in a dense, low-gravity atmosphere.

- Science payoff: direct sampling of organics that inform theories about life’s building blocks.

- Broader impact: data will help interpret observations of distant exoplanets and cold worlds in other systems.

Future missions will likely target Enceladus plumes, ring chemistry, and magnetospheric processes, continuing the steady chain of international collaboration and successive spacecraft exploration across the saturn system.

Conclusion

This ringed giant anchors the outer solar system with dramatic weather, wide rings, and a lively family of moons.

As a planet, its atmosphere and internal heat drive storms that span hours to years, while fast rotation sets day-lengths measured in hours and long orbits that last many days and decades.

Its low density—despite immense size in miles and kilometers—comes from gas layers rich in hydrogen and helium. That mix makes this world behave very differently from planet earth.

Ring dynamics and recent mass limits reshape ideas about ring lifetimes. A saturn moon like Titan and active saturn moons such as Enceladus open new paths to study organics and habitability.

Keep watching: Dragonfly and future missions will deepen our view of rings, atmosphere, and moons across the wider planetary system.

Connect me